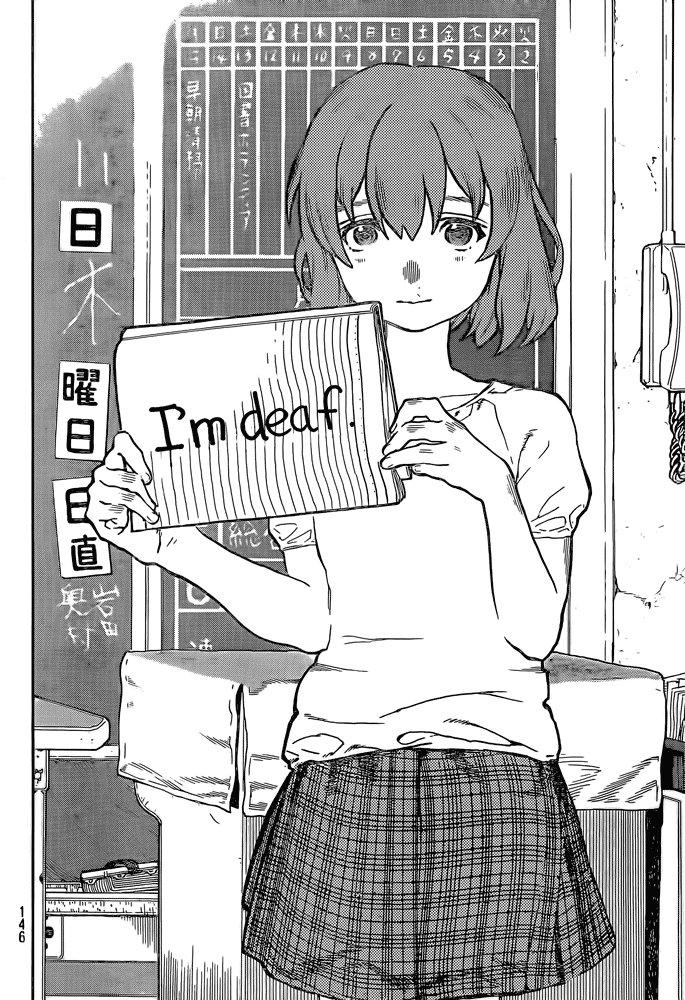

I’ve been putting off writing my A Silent Voice review mostly because I’m really sick of thinking about A Silent Voice and also because I’ve been interested in watching other movies. Like, a ton of other movies. I’m just not interested in A Silent Voice no matter how you swing it, and that’s coming from someone who thoroughly appreciates the original One-Shot and marginally enjoyed reading the 7-volume manga. I have engaged a wealth of A Silent Voice content in my time, and revisiting A Silent Voice for a Patreon-voted podcast episode, while obligated because fans voted for it, was really something else. That something else being a truly miserable time.

I intend to keep this short – or, as short as can be – because I’ve largely explained my general case against A Silent Voice in our Cinematic Doctrine podcast episode on the subject (shared above). But, here’s a rough, succinct elaboration on the entirety of A Silent Voice: it’s one-shot, it’s manga, and it’s film adaption:

The One-Shot:

- A short, poignant, reflective material on adolescent ethics and the natural maturity of growing up. Explores shame and guilt and how often the lessons and motivations learned from shame and guilt are fundamentally predicated on happening after the event that causes you to experience both shame and guilt. Shame asserts the inquiry “Why did I do that?” and guilt incurs the observation, “I’ve done something wrong”. Both often lead to motivation of change, change that one likely wishes they had engaged before doing the action at all. However, these emotions work as they do: they appear after an event. The One-Shot very much showcases the event (the bullying) and then gracefully ponders emotions (shame and guilt).

- The One-Shot is open ended in its ending, offering a far more intimate, real-life depiction of where most people are in their journey. We are all familiar with shame and guilt, but there are very, very few people familiar with the resulting motivation produced by such emotions. The One-Shot ends when Ishida meets Nishimiya as a teenager. The interaction there-after is further explored in the manga and then subsequently, yet truncated, in the movie. For me, the open-ended “incomplete” (quotations because I don’t think it’s actually incomplete) nature of the One-Shot proposes a question: If you feel similarly, what will you do? Ishida, although he doesn’t say anything to Nishimiya in this version of events, is already much further ahead most readers in his personal transformation: he’s seeking amends. The one-shot of A Silent Voice, as its titled, functions similar to a mirror; it shows you where you may be but cannot show you what’s next. Although we may be motivated to grow, we cannot be guaranteed growth. We may complete the work of sowing many seeds but what growth comes without rain?

- Most importantly, the fiction is good. By fiction, I mean the literal story divorced from metatextual commentary. The story in the One-Shot is a good little tale of shame, guilt, growth, and the likely-hood of maturing through adolescence. It’s just a good story, and even if someone doesn’t step away moved, they’ll likely put down the One-Shot with satisfaction.

The 7-Volume Manga:

- A welcome victory for female mangaka everywhere, the A Silent Voice manga invites a female perspective to an otherwise male-crowded medium. The lack of inappropriate material throughout the manga is in stark contrast to other manga regarding young-adult material of a similar vein, and a part of me is convinced that is due to the lack of “male-gaze” inherent to the gender of the mangaka.

- An unnecessary albeit interesting expansion on the One-Shot, the 7-Volume manga explores not only Ishida and Nishimiya’s aftermath of their elementary time together but also explores how others may respond to their guilt and shame. However, these various responses become debilitations to good fiction. Characters become caricatures of ideology and commit actions so strange and so unexpected that it can only be explained by metatextual commentary. In other words, the fiction is sacrificed for what the mangaka wants to say, that being an extension of Nishimiya’s bitter cry during the fight in elementary school, “I’m just trying my best!”. And yet, as everyone tries their best they are also doing terrible, awful, nasty things, narratively culminating in the ideology that moral absolutism doesn’t exist. Or, that since everyone is just trying their best, even when their best includes brutalizing the deaf, we can all just get along and forsake responsability and consequence (an ironic ideology when considering the literal A-plot of the manga). Which begs the question: why write a manga if you just want to say things so overtly that it sacrifices plot and sense? Write a dissertation. Write a paper. Write a non-fiction exploration on shame, guilt, and trauma-responses. Nonetheless, some scenes come out looking alright, despite other scenes coming out looking geriatric.

- Unfortunately never satisfies the promise of a romance. Although A Silent Voice will sometimes be celebrated for not having romance function as a B-or-even-C-plot, A Silent Voice is begging for some form of romance, or at least relational intimacy. So much about the pursuit of maturity and reconciliation is explored though relationship, and while the title itself is a play on the fact that so much is felt but never said, there is also so much to be explored that never will so long as the characters never finally become romantically involved. Additionally, there’s a whole wealth of problems created in romantic relationships not explored by never having Ishida or Nishimiya romantically involved, many of which could be explored in far more complicated, nuanced, and ultimately more natural ways. Yes, this may be built upon a more personal gripe, but I can attest to the unique struggles suffered unique to romantic relationships that otherwise are never felt in friendships. Not only my own marriage but several, several others. Exploring shame, guilt, and motivation is made so much more when characters espouse love. Love challenges and transforms shame, guilt, and motivation in every sense.

The Movie:

- A run-on sentence for the one-shot. A Silent Voice simultaneously overcrowds itself while having very little to offer. Like a balloon overstuffed, it pops and shrivels. A Silent Voice functions like a slide-show glance of moments from the manga, picking only a handful of what would constitute tear-jerkers or giffable moments. Not surprising at all from a studio like Kyoto Animation whose pension for over-animated moe-blobs to go absolutely over-board with the material. A Silent Voice is terminal emotional manipulation, stage-four beauty-porn. It cannot be engaged in a multi-faceted manner because it’s so in your face about what it’s about. The open-ended exploration of themes are gone from the one-shot and completely replaced with “beautiful” piano renditions confirming to you the joy or sadness you’re supposed to feel at the moment. If the one-shot could be a meditation for adults about where they’ve left their shame and guilt back in grade-school or college, the movie is for children who are overcome by bright colors and happy melodies.

- A devastating cherry-picking of several arcs from the manga, the movie treats the narrative iconography of A Silent Voice almost like modern Star Wars points at a robot and says, “remember that?”. It begs you to remember because it has nothing else to show you. Whole characters with individual growth are removed for the sake of seeing someone you liked animated. Whole characters go absolutely nowhere in terms of their own narrative arc and act like training-wheel versions of themselves. Then, before you can realize there’s nothing in these characters, the film does the worst thing possible-

- The abuse and evisceration of Nishimiya is wholly inexcusable when compared to the material present in both the one-shot and the manga. Yes, the one-shot codes Nishimiya as an object. Functionally, Nishimiya is the object of scorn to introduce conflict to the plotline of A Silent Voice. The true conflict is present in Ishida’s treatment of Nishimiya, but Nishimiya functions as a narrative tool for introducing conflict. Ishida merely instigates conflict. The one-shot, then, asserts how despite her narrative function is that of an object, her actual function is that as a human being: the human being you, the reader, may have mistreated or exploited in your time. Therefore, Nishimiya is coded as an object but not functionally an object. The manga, then, helps invigorate Nishimiya out from being an object and into a character. Nishimiya is no longer a sum of her parts: deaf and cute. Nishimiya has goals, motivation, thoughts, hopes, flaws; she is a character and not an object.

The movie, however, not only returns to the objectification of Nishimiya but relinquishes her character entirely. Nishimiya is treated solely as an object for scorn, suffering true abuse seperated from character. Even her decisions are no longer decisions made by a character but solely by a caricature. The movie takes the worst potential and actual parts of its predecessors (object-nature of Nishimiya and metatextual caricaturing of characters respectively) and implants them squarely on Nishimiya. Now she is reduced to a deaf cute moe-blob who only exists as an object for – not Ishida – the audience. Nishimiya becomes the object of audience manipulation; both to manipulate the audience into emotional reaction and to be manipulated by the audience as they fantasize about helping her. The title is imbued in the mere concept of Nishimiya, the true silent voice, one who simply exists as the single worst caricature in the film: a cute deaf girl. Offensive does not even begin to describe the sort of feelings produced within me over such a depiction of disability, one that was at least partially fair in the manga yet wholly stripped of maturity.

- The medium is the message, and the media here is film. Film is an entertainment medium. Yes, film can educate and produce meditations on “higher concepts”, but film is entertainment. Because of this, one presses play to enjoy, relax, or seek some other form of positive experience (or, a wanted experience). Nobody ever starts a movie with intention to dislike it, including a movie they suspect they won’t like (for, then someone would be vindicated of their dislike, and thus come away with a positive response), With this in mind, one is going into the media as one is creating the media: with intent to produce positive experience. Nishimiya is constructed to produce a positive response, a wanting response to the audience, and when you play with something like a disability to create that response, you have to be very careful. To see the function of the disabled fetishized in this manner feels incredibly wrong. Yes, the material is more about Ishida, but the abuse of Nishimiya is deeply problematic, inappropriate, and immoral when constructed under the medium of film, let-alone this film. To force feed so much information about how one is to feel about these situations through the manipulation of the medium (imagery and audio) is ironically absurd when one of it’s celebrated subject-matter is the deaf and disabled. Ableist privilege is easy to manipulate when the ableist will never know what it has until its gone.

Want more Christian-influenced media coverage? Subscribe to the Cinematic Doctrine podcast on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast app!

Consider supporting Cinematic Doctrine on Patreon! As a bonus, you can gain access to a once-a-month movie poll where you decide a movie we discuss on the podcast, early unedited episodes of the podcast, and merch!!

Melvin Benson is the Founder, Editor-In-Chief, and Lead Host of Cinematic Doctrine. Whether it’s a movie, show, game, comic, or novel, it doesn’t matter. As long as it’s rich, he’s ready and willing to give it a try! His hope is to see King Jesus glorified as far as the east is from the west!

Cinematic Doctrine is available on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, and other major podcast apps.

Leave a comment