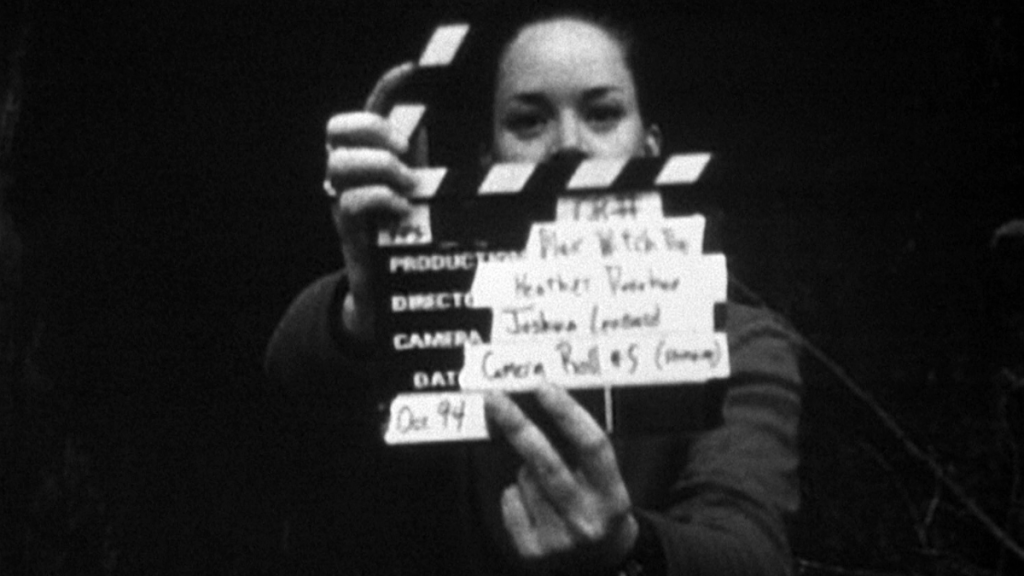

In early 2023, New York Times published an interesting little piece where-in the director for The Outwaters and the director for Skinamarink interviewed each other, as well as had some probing questions from the man hosting the interaction. But, while I had been hearing buzz about Skinamarink, I had heard nothing about The Outwaters other than learning it was a similarly strange indie-horror feature making its shocking rounds across the country. It hosted a few stark screenshots from the film and I was immediately intrigued, and the offering of a desert primary as a setting for some really wild material got me excited. While I was reading that in February, it wouldn’t be until September that I had the chance to watch the film, and while The Outwaters offered a wealth more of dialogue compared to it’s abstract, insular counterpart, there is undoubtedly similar qualities in both execution and experience between the two films. I’ll share a lot of my experience and interpretation below, but I also want to make clear that this is not a comparison review. I am not intending to focus or re-review Skinamarink when really I just want to talk about The Outwaters. I’m not a superfan of association with material mostly because it dries out the focus from the subject. So, I’ll mention a few things here and there, but my main focus is near 100% on The Outwaters. Lastly, I have also watched the two short-films released this year that showcase a combination of prequel and current-time material, and while I think it’s fair to say it isn’t possible to spoil something so aggressively cryptic, I will be making mention of what happens in those shorts (or, at the very least, allude to them) because it helps contextualize so much of how I feel about The Outwaters. But again, please trust me when I say any allusion to them will really only be pertinent to what I have to say and will not spoil anything because even the big criticism of the project is how archaic and borderline indecipherable it is.

The Outwaters is about a group of millennial artists traveling into the Mojave Desert to film a music video. The music video is simultaneously professional (filled to the brim with talent) and DIY (no permits, an intended quick weekend in-and-out job), which for a film set in the horror genre is always a recipe for disaster. What becomes difficult is defining the disaster that strikes, and, similar to Skinamarink, there’s a clear confidence and comfortability in letting the audience struggle and strain to find out what that disaster is. A routine criticism I have repeated throughout the year as I watch weird commentaries for movies nobody likes is that these directors will sometimes say, “I made this editing choice/narrative choice because I suspected audiences might be confused, so I wanted to make sure it was clear.” which almost always ends in the director making a worse-off decision (see: Beckman and Truth or Dare). Here, Robbie Banfitch races Kyle Edward Ball in the grand annual Let’s-Make-The-Audience-Work-For-It competition and boy is it brutal stuff. Despite my own thoughts, I agree with the criticism levied against the film. I clearly like the film, as my Letterboxd rating is both a 9/10 and a “favorite”, but I 100% completely understand – and even somewhat agree with – the criticisms levied against The Outwaters, primarily IllMakeYouLaugh’s short comment, “Longest ad for the worlds worst flashlight”. One of the first things I commented to my wife about the movie was how insidious it is for the filmmaking team to embrace the beauty of practical effects while utilizing the literal worst flashlight I’ve ever seen utilized in a film. It’s practically an off-beat anti-comedy joke that the flashlight is literally ginormous, too. Imagine putting in 4-D batteries for the width you get from this. Holy cow.

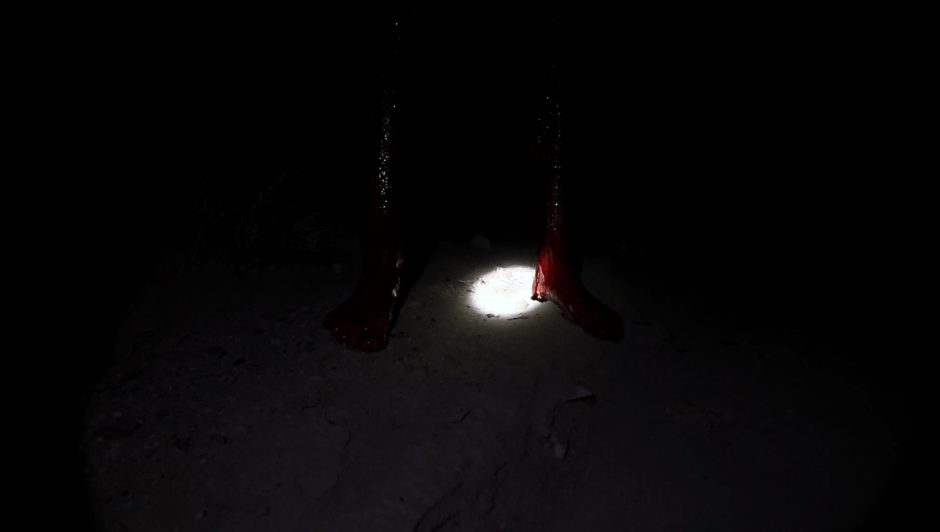

Flashlight aside, I think I would have been sitting forward with immense focus even if I could see 20% more (which would still only be about 15% of your television). The Outwaters takes some time to get the ball rolling but once things start happening it gets really chaotic. Pitch black screams in the middle of the night cascading across the flat, dusty Earth while the sound of bludgeoning and weeping refuses to quit, and the only sign that someone else may still be alive is the empty crimson puddles pooling in the dirt. From then on out it’s a mish-mash of artistry and interpretation, and if spending your time watching a film working doesn’t sound fun, who could blame you? For nearly an hour and a half you’ll be hearing non-descript noises alluding to violence against others, the potential presence of something frightening, and grimdark visuals set in the blistering sun of the Mojave. We’re far beyond non-linear storytelling and straight into non-constructive storytelling; a narrative whose indirection is it’s challenge and reward. Although, I must contest, the film is linear, insofar as it is comprehensible (of which both are debatable). That is to say; the movie, to me, clearly has a tone, a theme, a meaning, a purpose, all the things a movie typically has. In that respect, it’s a highly understandable piece of media.

For instance, the premise alone (artists making a music video) alludes to some kind of passion or focus of the film. The original goal of our heroes was to make music. Additionally, there are plenty of moments in which our characters sing music amidst all kinds of emotion, whether sadness or joy, melancholy or companionship; music is huge in The Outwaters. And, while The Outwaters will cut short the creative lives of our characters, the purpose and utilization of sound as a not only a tool but motif is present throughout the film. Early on our sound-guy (and director) Robbie puts a microphone into a hole and listens. It’s a great moment of tension and anxiety as a knowing audience is preparing for the worst, but little moments like this (of which there are several) assert a fixation on sound. It’s no surprise, then, that the film discards visuals near-entirely to bombard it’s audience with horrific, graphic, and truly vile audio, only using visuals to introduce the smallest tidbit of knowledge to improve your sense of fear. While I’m not too keen on every visual used here, there is nothing that goes without waste or purpose, as the power of lighting permits a true sense of focus, where-as sunlight can cause a lot of misdirection and misfocus on what we want to see. But, no worries there considering the sun is gone for roughly an hour of the film. So, sound and the way in which we understand and relate to it is huge.

Secondly, the film has a fairly recurrent theme of motherhood, or at the very least of matriarchal authority/influence. Our lead singer mentions her mother several times in the film. This is to some audience member’s chagrin, of which I can understand despite the film being found-footage. We’re seeing bits and moments in a group’s life, and the process of editing in-world will draw out only what the proverbial editor will believe is important to understand our world. And while the film has difficulty in asserting who is showcasing these events (a la MarbleHornets where-in someone is vlogging found tapes alongside vlogging paranormal events in their life, thus creating a “convincing” real-world reason for us to be witnessing the events) or editing them, or even adding audio to certain parts or releasing the shorts afterward, there is still good reason to accept a characters verbal meditations on their mother. If I recall, the music video they’re shooting is about a song written for her mother (who had passed), so I just felt inclined to reject that criticism even if it could still be annoying to hear so much. But, but, but; the film has a theme regarding mothers, and apart from the music being about mothers, this character pleads for her mother’s help during a tragic night, the film has iconography of impregnation, the director’s mother is in the film as his character’s own mother (who is also featured in more than one scene, and also featured as the prominent-yet-disfigured face on the poster), and while this one may seem a stretch, I do believe the “Mother Earth” is a present matriarchal figure of the film. Particularly, in one scene later in the film our character seems to have stumbled and fallen into something, or perhaps he was eaten (which, sidebar: my memory of the film would have been this much a blur even if I had just recently watched the film), but we hear him splash into something before turning the camera light on. He’s chest-deep in a pool of red-liquid, a blood pool of some kind (or so I interpret), and there’s even the glowing, glistening visual of a chasm opening with a bright light piercing through (seen in one of the alternative film posters). All of this iconography is very crude and grotesque, aggressively reminding the viewer of their biological state amidst a modern world of technology, and I feel as though our characters getting lost within the brutal indifference of nature itself catapults our minds into thinking about “Mother Earth”.

I do think the fascination with motherhood may extend to a fascination with women, as well. That is not to say the film is misogynistic – that it is idolizing, idealizing, or commoditizing women – but that the film seems very gender conscious in one of the most bizarre and downright abstract ways I’ve seen in years. Even Barbie commentates on (at the very least binary) gender types in a strange manner but nothing comes quite so close as The Outwaters. And I am aware that Robbie Banfitch at the very least skims some reviews so maybe he’s reading this and chuckling going, “Uhh, I wasn’t thinking that but your perspective is curious, go on!”, or maybe he’s like, “This hack is writing too much.” (which is also fair. I am a hack!). But, without spoiling, the film’s final moments – the literal visual conclusion of the film of which those who have watched know exactly what I’m talking about – utilizes gender to create a very memorable moment. And, in this way, creating almost a rejection of assigned-at-birth gender-politics; or, to put it bluntly, an overt trans statement regarding the concept of gender at all. In which case the whole film is allegorical for the extreme turmoil of coming-out, being plagued with a combination of either sexual or gender confusion. Maybe even a pleading to be reborn. And while I can’t recall if the characters discuss life-after-death or reincarnation, one character does panic and mutter the Lord’s prayer. Sure, it’s a horror movie, people do that all the time, but The Outwaters is very assertive at making points. I wasn’t lying earlier when I said the film uses practical effects: it’s all practical effects (source: Banfitch’s Insta). In this way, I am comfortable assuming the repetition of saying the Lord’s prayer is an earnest knowing of, at the very least, some doctrinal knowledge (although the character clearly doesn’t know the Bible isn’t a magical book, and thus the repetition of the Lord’s prayer as though it were a spell would be useless in such a desperate situation. Granted, the character would also just think the Bible is useless in general), and thus understanding that the metaphorical concept of rebirth is present within the Scriptures.

So, all this to say, renewal, rebirth, a return or restart is present within the film, something that all of mankind has at some point yearned for. And, while I can confidently say, in part, the Scriptures do propose a kind of rebirth (insofar as human understanding can explain and understand), the world itself has no category for such an existence. It is all theory, a pondering, a thought lost among the dead who have nothing else to say other than silence. Except here, in the Mojave, where it seems the petrifying reality of such cosmic rebirth seems to be true, and I think in that way the film is quite clear: it’s this disgustingly stark image of rebirth and renewal. The first of the two short-films I think makes this abundantly clear, as the final moments end in a character’s failed attempt to connect with their partner. Robbie writes a letter to his ex stating that he thinks he’ll be better after he returns from the music video excursion. There’s this hope to be someone else, as his complaints to his friends are recurrent and relatable, a self-hatred of who he is despite being exactly who he is (the character, not the director. I am wholly discussing the character). It’s in this that I confess my entire understanding of the film may be poisoned by my present circumstance, for I am plagued with self-hatred, self-loathing, an unkindness toward myself for being myself, yet the recognition that I can be no one other than myself. As such, it’s possible that during my pursuit to understand The Outwaters I’ve actually just projected my own filter near-entirely. But, I’m also convinced of the film’s themes, too. It feels like a gendered meditation on rebirth, and even the film’s fairly risqué semi-cosmic sexual assault scene (that, by the way, is not as graphic as it sounds. Far less graphic than Evil Dead, which also isn’t that graphic.) comes across like a scene disgusted in the heteronormative, or at the very least a nightmare sequence where-in Robbie is envisioning this nightmare reversal where-in he is female and thus being taken over, which would further assert the films literal final moments as rejection of the self and a pining for rebirth.

Look, I went off the deep end. The last few sentences are just actual insane talk. This film is crazy. It’s wild and weird and transgressive and disgusting and I even felt myself upset at times, but not upset to the point of discomfort or offense. I’m not a fan of seeing sexuality so starkly, nor a fan of nudity, but I can respect and interpret the artistry present even when the film gets cosmic and chaotic. But, this movie is wicked wild, and since seeing it I have been enamored with thoughts about the film. The movie is bonkers and difficult and challenging; and most of all, not worth it for most people. I don’t think everyone needs to like a movie, understand a movie, or like a movie they understand. There are plenty of movies people like that they don’t understand, so I really don’t want anyone thinking my read here is that people didn’t get it and thus don’t like it. That is so far from the truth. People just know this about me by now: I like movies that challenge me. Better yet, I love movies that challenge me, and The Outwaters has not only been on my mind for months, I’ve also been listening to the songs from the movie and short films, eagerly checking out Banfitch’s Insta for new insight into the film-making process, messaged the guy saying, “I liked your movie! I’m going to geek out and tell you what I think are some themes!”, and have been shopping around a way to have friends over to watch the film and discuss it. It’s just that kind of movie for me, and so it hits all the checks I look for in a film.

The Outwaters can be great, if not outright perfect in it’s unabashed acceptance of itself – an ironic reality for a film that I interpret is about the rejection, rebirth, and potentially failed renewal of the personhood and soul of a singular character – but it can also be downright awful as a film whose unconventional comfortability is borderline mean at times. I mean, there’s some awesome effects here that I almost feel like one could argue are wasted solely because they are barely visible. And, in terms of things I didn’t like, there was a sense of millennialism that was just so out of my wheelhouse, and I’m not talking about those “millennial comedy/Joss Whedon” style reels that trend every now and then. What I’m talking about is the discussions on vibrations as a sort of post-science/pseudo-science form of spirituality, where-in the concept of everything vibrating is the scientific equivalent to the soul in religion. Sure, the film has themes of sound and music, and thus has themes of vibration and motion – the ever constant motion of reality (which leads to the self-hatred of, “If everything is constantly vibrating, and thus moving, and thus changing, why am I still the same?”) – but I’ve personally interacted with a very psuedo-science individual (who never quotes studies, facts, figure-heads in their field, etc.) who talks about vibrations being “off” and thus their mood is bad, or how their “energy” (and not just protein based energy) is off, all based on (???). So, to me, that was a little difficult to see that in the movie.

The only other thing I’ll have to say (so far) about The Outwaters is that the film feels incredibly personal. As I described to my wife, “The Outwaters feels like a movie made specifically for the self, or for a select group of friends, and that even if it didn’t connect with anyone there would be a self-satisfaction in having made it with such precision”. This is an entirely baseless assertion on my part and, again, Banfitch could be reading and go, “No it for money $$$” but at the very least there’s this sensation of intimacy that the film exudes, almost oozes, and leaves me feeling invaded. I think in that regard there’s even more reason to affirm why so many are turned off by the film, because ultimately it may not even be a movie for any of us. But, again, even if this isn’t the case, this is just how the film came across to me. I wouldn’t be offended if I was wrong (and, hopefully, I am causing no offense), but it feels like the events are intrinsically personal.

Even so… what’s not to love? 2022 really was a great year for horror, and not because of some silly A24-esque girlbossification of slashers nonsense, but because the indie-sphere is popping out some of the most uncompromising material I’ve seen in a very long time, and I cannot wait to see what’s in store for the future of this horror space. While everyone’s imitating The Babadook – another irony considering the contract for that film dictates no sequels are permitted – my excitement resides in the wildly weird world of The Outwaters and Skinamarink (as well as a side of more Saw and Evil Dead lol).

Want more Christian-influenced media coverage? Subscribe to the Cinematic Doctrine podcast on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast app!

Consider supporting Cinematic Doctrine on Patreon! As a bonus, you can gain access to a once-a-month movie poll where you decide a movie we discuss on the podcast, early unedited episodes of the podcast, and merch!!

Melvin Benson is the Founder, Editor-In-Chief, and Lead Host of Cinematic Doctrine. Whether it’s a movie, show, game, comic, or novel, it doesn’t matter. As long as it’s rich, he’s ready and willing to give it a try! His hope is to see King Jesus glorified as far as the east is from the west!

Cinematic Doctrine is available on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, and other major podcast apps.

Leave a comment