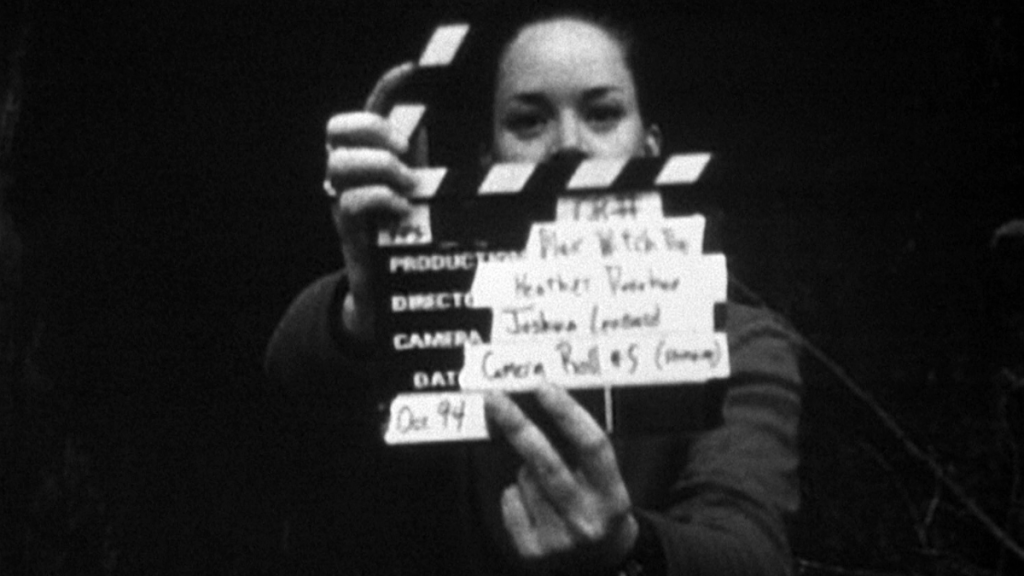

The Blackcoat’s Daughter is uncompromisingly slow and I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in this House even more so (to the point of outright breaking people, honestly), and Gretel & Hansel felt a lot like Perkins becoming familiar with, let’s say… more conventional ideas of pacing. Unfortunately, I don’t think Gretel & Hansel came out very strongly, probably being my least favorite of his flicks, but it made sense to see him try something more commercial. If he wants to keep making movies at this caliber than he needs to be accessible. Then you have Longlegs which comes out with this incredible marketing push, exciting cast, and is a fairly decent movie overall. I think Longlegs is a little too much like The Blackcoat’s Daughter in terms of themes, ideas, and overall oppressive nature, and that all felt disappointing to me, but it was a good effort and solidified a lot of what I’ve come to understand about his style. Lastly, we have The Monkey, which honestly is one of my favorites he’s done, completely throwing many for a loop as this wildly strange horror comedy that feels like a mix of time periods and filmmaking styles. Perkins’ interests in the macabre are clear, playing with witches, incredibly impressive visuals, and an easy pace to boot.

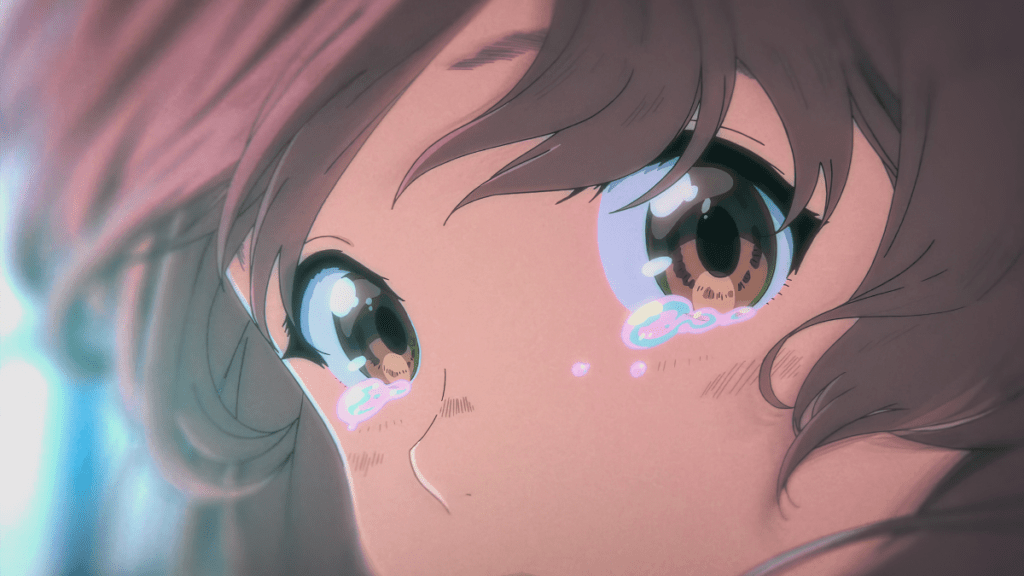

Keeper brings us back from The Monkey to his slowburn psychological horror stories, easing itself into a semi stuck-in-impossible-to-escape-scenario film. The Monkey stood out as his only male-led story, and with Keeper we return to him telling more women-oriented stories. Horror has always fetishized the female lead, for better and for worse, but Perkins has a good head on his shoulders when it comes to telling gender-oriented tales. His directing career has practically been built on it. Keeper is no different, expertly drawing out Tatiana Maslany’s impeccable acting showing a variety of anxieties a woman cautiously experiences when alone with a known or unknown man. There isn’t any humor here. Not unless you count any gendered awareness between the sexes.

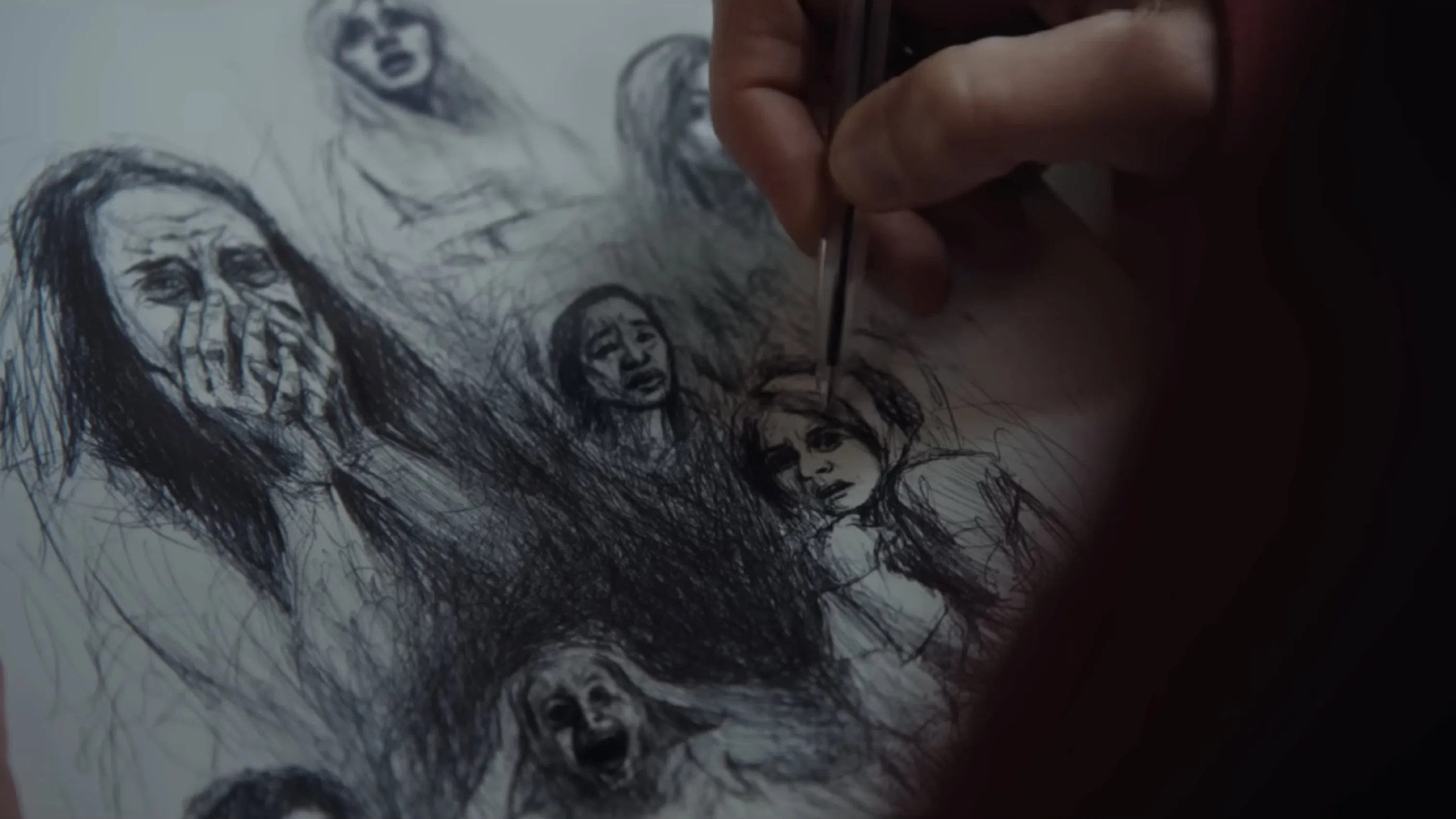

Longlegs, with its abstract imagery and ideas, felt like verbiage. It felt like gobbledygook, and I think the movie knew that, too, because it’s third act feels so disparate from the rest. That may seem ironic, considering the archaic marketing, but I believe that to be true. It kinda meant nothing. Here, Keeper has abstract imagery but it’s operative ideas are dreamlike. They don’t mean “anything” in that they aren’t definitive. Their meaning is inherently subjective. Scenes of Maslany laying in a tub overlayed with a river washing over her, light shining bright like a sun setting behind a single tree all while the sun is actually still noontime; there’s a lot of things here that remind me of Panos Cosmatos’ filmmaking style; you do it cause it looks good and evokes something. Perkins has done this before, and it felt like Longlegs was too clinical, bordering on saccharine, to really embrace their filmmaking benefits. At 1h39m, I do think the movie plays a little too much, but I think it’s still a worthwhile, patient film.

Also, and I’m saying this as someone who grew up a man, so correct me if I’m wrong, but Perkins’ feminist ideas he explores are much deeper than most films. A lot of filmmaking, being an industry born and bolstered in the West, is very capitalist. Inherently so. Even when filmmaking wants to be used to deconstruct cultural ideas or propagate others, it still carries this internalized capitalism. As an example, a story about a woman becoming her own through life, work, and luxury is an empowerment story, yes, but it is still empowerment through commerce and the benefits therein. That’s capital. Same would be true if a story is about a woman competing with others and, through their socially-effeminate benefits, succeeds over another. Capitalism is a form of competition. That’s capital. Independence and making oneself are good things, but that’s merely humanity itself. Yet, something unique to the biologically female experience is childbearing, and in a capitalist ideal that focuses on short term high profit gain, the fact that women bear children for 9 months, diminishing their workload, and then recover from birth for several months to several years, a capitalistic society has to understand there’s only so many quarters in a year before that’s a problem.

I’m speaking in capitalistic terms. I don’t believe in this, by the way. It’s akin to buying slanted toilets in an office bathroom so your employee doesn’t get too comfortable. It’s putting a snack bar in so people’s breaks aren’t too long. The mere idea of people being human is abhorrent to the capitalist. Humanity doesn’t make money. Money makes money. And if you’re not money, then get out of the way.

Money doesn’t get pregnant. But women can get pregnant. And I think there’s something holistic about how Perkins talks about womanhood in his films. As my wife has described him before, he’s a male director and writer who “gets it”, and the way he explores womanhood in Keeper dives a little more into pregnancy than any of his previous films. It’s not the whole movie, but it’s a big part of it. Because pregnancy is hard but it’s also beautiful, too. But it’s a choice. It has to be a choice. But what’s so upsetting for women as the gender that gestates a child, there are so many things about how women are treated that rightfully bring caution to mind. For, if a 9-month pregnant woman were to, say, rest their feet in a nearby lake, relieved to feel water rush through their toes rather than feeling the increased weight on their achilles, what kind of vulnerable state might she be in? And to those who desire evil, what ruminations fill their mind? So much opportunity for evil.

It is no mistake that the film opens across time. We see multiple women across multiple times periods, and how women have been treated over and over by many men has been clear; better a dead woman than a disobedient woman. Women, to many men, only have value insofar as men have power over them. Even the navigations women embrace against such suffering hasn’t changed. Playing dumb, playing coy, playing smart, smiling, and, quite frankly, having to practice a clever cautiousness. Because being authentic invites danger. A sinful heart doesn’t want to celebrate beauty, it wants to possess it. And when it cannot possess it, it wants to kill it; better a dead woman than a disobedient woman.

Natural birth sometimes took place at a lake or a river, using the setting as an advantage. It’d be cleansing, refreshing, and easy to position oneself. Now, woman are propped up on a table, on their backs, in a position that is largely unsuitable for childbirth. It positions the body in such a way that is more difficult for the woman, and it also eliminates the use of gravity to assist in the process. No, women are on the table because it was easier for the doctors, typically male, to handle the procedure. I mention this not only because it’s one small way in which patriarchal decisions have negatively impacted women in women-specific areas, but also because the film opens with a discussion on childbearing, is a drama about a will-they-wont-they relationship, and has other imagery and allusions to childbearing/birthing. And also because Perkins has played with some of these ideas before (The Blackcoat’s Daughter).

In the end, concessions have often been made by women at the behest of men. Childbearing is no different, as often it’s been interpreted as continuing the man’s legacy and lineage. Yet children are as much a mother’s as they are their father’s, if not more so. Men can shoot their seed on a dime, but women’s contribution is much rarer, limited to a few possible chance days. A man may have many children, but a woman has her children. And when she chooses to have them, how she chooses to have them, and who she chooses to have them with is a rightfully sacred thing.

Keeper is a psychological drama dressed in horror, a film that will no doubt disappoint some who wanted something more bombastic a la The Monkey or pseudo-cryptic like Longlegs. To me it was exactly what I wanted; Osgood Perkins making choices about what he likes, what he wants to explore, and ignoring conventions when necessary. Although it isn’t as risky as I Am The Pretty Thing That Lives in This House, it’s much better paced than Gretel & Hansel, and generally more interesting than anything he’s done since The Blackcoat’s Daughter. And after The Monkey, which I thought was a great time, I’m really happy to see Keeper continue his stride into the abstract. I hope he’s able to do more quiet little weird movies like this. His voice is so fascinating and I don’t think anyone’s really making movies like him.

Want more Christian-influenced media coverage? Subscribe to the Cinematic Doctrine podcast on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast app!

Consider supporting Cinematic Doctrine on Patreon! As a bonus, you can gain access to a once-a-month movie poll where you decide a movie we discuss on the podcast, early unedited episodes of the podcast, and merch!!

Melvin Benson is the Founder, Editor-In-Chief, and Lead Host of Cinematic Doctrine. Whether it’s a movie, show, game, comic, or novel, it doesn’t matter. As long as it’s rich, he’s ready and willing to give it a try! His hope is to see King Jesus glorified as far as the east is from the west!

Cinematic Doctrine is available on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, and other major podcast apps.

Leave a comment